Through the Lens of Scripture

The Bible is the only true source of doctrinal authority for Christians. Its authority originates in its divine character; therefore, the subject of “inspiration” is of prime importance for Christians. As we will see, the Bible is also the best source for learning about its texts—as it offers direct statements about its divine authorship, canonization and preservation.

While other Scriptures might immediately relate to this topic of study, only II Timothy 3:15-17 explicitly declares that the biblical texts are God-breathed, as Paul writes to Timothy: “And that from a child you have known the Holy Writings, which are able to make you wise unto salvation through faith, which is in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is God-breathed and is profitable for doctrine, for conviction, for correction, for instruction in righteousness; so that the man of God may be complete, fully equipped for every good work.”

In addition, II Peter 1:19-21 encapsulates how it was written: “We also possess the confirmed prophetic Word to which you do well to pay attention, as to a light shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star arises in your hearts; knowing this first, that no prophecy of Scripture originated as anyone’s own private interpretation; because prophecy was not brought at any time by human will, but the holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.“

Throughout our study, the word “inspiration” appears in quotation marks. The reason for this stylistic notation is because the word and its various forms do not adequately describe the divine character and quality of Scripture. This character and quality is better defined as “God-breathed.” However, due to its popularity and to avoid confusion, we continue to use the term “inspiration” to describe the entire process by which Scripture became God-breathed; it is used interchangeably with the expression “divine authorship.”

Every Part of Scripture Is God-breathed

The first truth concerning “inspiration” is that every part of the biblical writings (letters, syllables and words) is God-breathed, each part no more or less than the other. Greek scholar Spiros Zodhiates explained that the English word “all” in II Timothy 3:16, which is translated from the Greek word pasa, means “every part of the whole and all of it together” (Zodhiates, “graphe,” The Complete Word Study Dictionary New Testament, p. 382). An amplified translation of this passage could read “Every part of the whole and all of Scripture together is God-breathed” (Ibid.).

The apostle Paul confirmed that divine authority extends even to the grammatical forms of words. In his teaching on the covenant of promise in Galatians 3:16, he made the distinction between Abraham’s seed (Gk., spermati) and seeds (spermasin). The Greek word endings ti and sin differentiate between one grammatical form of the word and another (singular and plural), effecting a specific teaching. The noun “seed,” whether in Hebrew, Greek or English, can be used in a singular, collective or plural sense. Paul’s argument was that in some Old Testament passages (Gen. 3:15, 22:18), seed refers to Jesus Christ, the chief representative of Abraham’s offspring. This conclusion is affirmed by Paul’s declaration a few verses later: “For you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28).

The late B.B. Warfield, former professor of theology at Princeton Theological Seminary and a leading scholar on the Bible’s divine authorship, wrote: “No doubt it is the grammatical form of the word which God is recorded as having spoken to Abraham that is in question. But Paul knows what grammatical form God employed in speaking to Abraham only as the Scriptures have transmitted it to him; and, as we have seen, in citing the words of God and words of Scripture he was not accustomed to make any distinction between them…. [It] is possible that what he [Paul] here witnesses to is rather the detailed trustworthiness of the Scriptural record than its direct divinity—if we can separate two things which apparently were not separated in Paul’s mind” (Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 2, p. 844, bold emphasis added).

Jesus underscored the emphatic present tense of the Hebrew verb in Exodus 3:6 when defending the resurrection of the dead in his argument with the Sadducees, which is preserved for us in Matthew’s Gospel (Matt. 22:23). Near the end of this interchange, Jesus said, “Now concerning the resurrection of the dead, have you not read that which was spoken to you by God, saying, ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’? God is not the God of the dead, but of the living” (Matt. 22:31-32). Again, the difference of a few letters in the Greek text would have altered the meaning of this passage.

By focusing on the present tense “I am” and “God is,” Jesus emphasized the perpetual covenant and promises God established with all three patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac and Jacob). In order for Him ultimately to fulfill His promises to them, they “must rise and live again in the resurrection in order that He may be their God. This is what the Lord [Jesus] set out to prove (in v. 31) ‘concerning the resurrection’ ” (Bullinger, The Companion Bible, p. 1360).

Both Jesus and Paul showed an acute awareness of the minor details of the Hebrew and Greek texts. These details have a special purpose in God’s revelation of truth, and the authors of the Bible recorded them for both our edification and salvation.

Every Scripture Is Equally God-breathed: Some have erroneously considered certain biblical segments, such as the genealogies of the primitive, patriarchal and regal periods in I Chronicles to be less a product of divine authorship than others like the Gospels. However, the differences between the various segments of Scripture are not a matter of “inspiration,” but of purpose.

The four Gospels, for example, provide us with a record of the words and actions of Jesus Christ that form the basis of salvation (Luke 1:4; John 20:30-31). According to scholar Norman Geisler, the book of Chronicles in comparison provides 1) a priestly religious history of Judah; 2) teachings of the faithfulness of God, the power of His Word and the essential role of worship in the life of God’s people; and 3) a record of the Davidic kings and their descendants through whom the Messiah would come (cf. Matt. 1) (Geisler, A Popular Survey of the Old Testament, p. 149). Though less explicit, Chronicles also offers a typological view of the temple that points to Jesus Christ and the Kingdom of God. When viewed in this light, it is clear that Chronicles is equally divine in nature and has a historical, doctrinal and Christological purpose that leads us to Matthew 1:1 and offers proof that God has fulfilled His promise of a Messiah.

The late John William Burgon, a textual scholar and Anglican theologian of the nineteenth century, best expressed this truism in his book Inspiration and Interpretation: “The Bible … is the very utterance of the Eternal … as if high Heaven were open, and we heard God speaking to us with human voice. Every book of it is inspired alike; and is inspired entirely. Inspiration is not a difference of degree, but of kind [purpose]” (p. 76, emphasis added).

Burgon adds that while the subject matter may change from one part of the Bible to the next, “it is a confusion of thought to infer therefrom a different degree of Inspiration…. [The] Bible must stand or fall—or rather, be received or rejected—as a whole…. There is no disconnecting one Book from its fellows. There is no eliminating one chapter from the rest. There is no taking exception against one set of passages, or supposing that Inspiration has anywhere forgotten her office, or discharged it imperfectly. All the Books of the Bible must stand or fall together.… And while you read the Bible, read it believing that you are reading an inspired Book—not a Book inspired in parts only, but a Book inspired in every part—not a Book unequally inspired, but all inspired equally—not a Book generally inspired—the substance indeed given by the [Holy] Spirit, but the words left to the option of the writers; but the words of it, as well as the matter of it, all—all given by God” (Ibid., pp. 102, 111-112, 114-115, emphasis added).

Only the Biblical Writings Are God-breathed

Another truth of II Timothy 3:16 is that only the written texts, the details and substance of Scripture, are God-breathed. The Bible describes the prophets, apostles and their scribes as having been moved, driven or carried along by the Holy Spirit in such a way that what they wrote were the literal words of God.

Both the Greek and English renderings of II Timothy 3:16 confirm this conclusion. Here the apostle Paul linked the idea of “inspiration” to the biblical writings with his use of the Greek word graphe. Translated “Scripture” in English, the word graphe for a handwritten document comes from the verb grapho, which means “to write.” The English word “Scripture” comes from the Latin word scriptura for the product of the act of writing (cf. Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary “Scripture,” p. 1056). In the New Testament, graphe is used 51 times to refer only to the written texts of the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures. In most of these instances, it pertains to a passage or the entire collection of the surviving copies (apographs) of the Old Testament writings. Four passages distinctly refer to the original documents (autographs) and preserved writings of the apostles and their scribes (e.g., I Tim. 5:18; II Tim. 3:16; II Pet. 1:19-21, 3:16).

In two passages, the Greek gramma(sin)(ta) refers to the writings of the Old Testament (John 5:47, II Tim. 3:15). Paul used grammasin to describe the written letters of his Epistle to the Galatians (Gal. 6:11).

Dr. J.I. Packer, professor of theology at Regent College, further explained the connection between “inspiration” and the biblical texts: “Inspiration is a work of God terminating [ending], not in the men who were to write Scripture (as if, having given them an idea of what to say, God left them to themselves to find a way of saying it), but in the actual written product. It is Scripture—graphe, the written text—that is God-breathed. The essential idea here is that all Scripture has the same character as the prophets’ sermons had, both when preached and when written” (Comfort, The Origin of the Bible, p. 30, emphasis added).

God’s revelation of truth for mankind resides not in the ink, writing materials (papyrus and vellum) and handwriting, but in the words written by His holy servants in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

Old Testament: God specifically chose Abraham with whom to establish His covenant of promise (Gen. 12, 15). God’s promises to Abraham were no doubt transmitted orally to his immediate offspring. With the limitation of human life spans after the Noachian Flood, apparently to about 120 years (Gen. 6:3), a more precise written revelation was needed of what Jehovah, the Covenant God, required of and promised to future generations of Abraham’s descendants. After God delivered His people from bondage in Egypt as He had promised Abraham (Gen. 15:13-15), it became imperative that the new nation possess a legal and religious system and documents that reflected its divine calling (Ex. 19:4-6). God began the process by making a covenant with the Israelites and producing a written record of truth. He revealed Himself to His people through direct communication and the visions and dreams of His holy prophets (Num. 12:1-8; Heb. 1:1). Over time, these words were written down and sealed as a testimony for God’s covenant people Israel.

Jesus’ discussion with the Jews in John 5 affirmed that the Hebrew Scriptures were the final deposit of revelation for the nations of Israel and Judah until the writing of the New Testament. Jesus stated: “Do not think that I will accuse you to the Father. There is one who accuses you, even Moses, in whom you have hope. But if you believed Moses, you would have believed Me; for he wrote about Me. And if you do not believe his writings, how shall you believe My words?” (John 5:45-47).

How could Moses, who had been dead for nearly 1,500 years, accuse the Jews of their unbelief? Ernest Martin explains that it was common practice for people during the time of Jesus and the apostles to “consider that a letter sent to a person or a group (or even the bearer of the letter) [be] looked on as if the writer were present when the letter was read” (Martin, Restoring the Original Bible, p. 395).

Though Moses’ writings had been copied for centuries, Jesus still considered them to be trustworthy in all their declarations and to carry the same divine authority as when they were first written. For Jesus, it was as if Moses was alive and personally accusing the Jews of their unbelief. Ironically, the Jews’ belief that Moses was a prophet of God (John 9:29) added weight to Jesus’ charge. Their refusal to heed Moses’ words in Deuteronomy 18:15, 19, pointing to Jesus as the anticipated Prophet, carried a penalty of divine judgment, which was executed over 40 years later when the Roman General Titus conquered Jerusalem and burned the temple to the ground. Jesus, the Jews and even Paul extended this same binding authority to other Old Testament writings on several occasions in their description of them as “law” (e.g., John 10:34-35, 12:34; I Cor. 14:21).

New Testament: The context of II Peter shows that the apostles and other New Testament writers were fully aware that their ministerial duties carried an implicit command to compose and compile an accurate testimony of their writings for the brethren before their deaths. Prior to the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD, God undoubtedly revealed to the apostles that Christ would not return in their lifetimes. This is evident by comparing the tone, tenor and content of their earlier and later writings. Peter’s urgency to complete his writings is apparent from his statement in II Peter 1:15: “But I will make every effort that, after my departure, you may always have a written remembrance of these things [the truth of v. 12], in order to practice them for yourselves.” Peter considered this task so important that he viewed failure to accomplish it as being negligent of his divine role as an apostle and a teacher of the Gospel (II Pet. 1:12).

The apostle Paul earlier wrote to the Church at Rome in 57 AD that his ministry carried the important responsibility of writing to the brethren. “So then, I have more boldly written to you, brethren, in part as a way of reminding you, because of the grace that was given to me by God, in order that I might be a minister of Jesus Christ unto the Gentiles, to perform the holy service of teaching the gospel of God; so that the offering up of the Gentiles might be acceptable, being sanctified by the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 15:15-16; cf. Eph. 4:12). This same attitude is also expressed, in varying degrees, by Luke, James, John and Jude in their writings (Luke 1:1-4; Jas. 1:19ff; I John 5:13; Jude 1:3, 5, 17; Rev. 1:1-3).

Within the first two decades of the Church’s existence (ca. 50 AD), the Epistle became one of the chief instruments for preaching and teaching. Paul directed his congregations and ministers (e.g., Timothy) to read and circulate his letters (Col. 4:16; I Thess. 5:27; I Tim. 4:13). The epistolary form allowed Paul and the other apostles to instruct, edify, correct and comfort many brethren at one time without being on location. Paul exhorted the brethren at Thessalonica to “stand firm, and hold fast the ordinances that you were taught, whether by word or by our epistle” (II Thess. 2:15). He also set his Epistles as the standard by which brethren were to measure themselves and admonish others: “Now if anyone does not obey our word by this epistle, take notice of that man and do not associate with him so that he may be ashamed” (II Thess. 3:14).

Peter likewise sanctioned the divine authority and character of the New Testament writings in declaring, “We also possess the confirmed prophetic Word to which you do well to pay attention” (II Pet. 1:19). This same truth is developed further in his Epistle where Peter explicitly placed the written commands (doctrines and teachings) of the apostles of Jesus Christ on the same level as the prophets’ words in the Old Testament writings (II Pet. 3:1-2) and equated Paul’s Epistles as Scripture (II Pet. 3:16).

By compiling their teachings in written form, the apostles and New Testament authors were creating a permanent record of their words through which future brethren would believe in Christ (John 17:20).

God Is the Real Author of Scripture

The greatest truth taught by II Timothy 3:16 is the divine authorship of Scripture. In the Greek, this passage reads Pasa graphe theopneustos, meaning “All Scripture is God-breathed.” The word theopneustos, often translated “God-inspired,” is found only in this passage. What does this word actually mean?

The commonly translated English phrases “inspired of God,” “given by inspiration of God,” and their variations are derived from the Latin words divinitus inspirata. Though not wholly inaccurate, these Latin-based words have obscured the real meaning of theopneustos. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia notes: “The Greek term has, however, nothing to say of inspiring or of inspiration: it speaks only of ‘aspiring’ or ‘aspiration.’ What it says of Scripture is, not that it is ‘breathed into by God’ or is the product of the divine ‘inbreathing’ into its human authors, but that it is breathed out by God, ‘God-breathed,’ the product of the creative breath of God. In a word, what is declared by this fundamental passage is simply that the Scriptures are a divine product, without any indication of how God has operated in producing them. No term could have been chosen, however, which would have more emphatically asserted the divine production of Scripture than that which is here employed [i.e., Godbreathed]” (Bromiley, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 2, p. 840).

Paul’s usage of theopneustos in II Timothy 3:16 links the idea of the breath of God with the writings (graphe) of the biblical authors. In this passage, the Greek word theopneustos is used as a predicate adjective, which means it modifies or describes the word “Scripture” (graphe). Thus, every part of Scripture possesses the quality of being God-breathed.

This first-century understanding is graphically portrayed in Jesus’ statement during His temptation by Satan: “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word [utterance] that proceeds out of the mouth of God‘ ” (Matt. 4:4). The context of Hebrew 3-4 reveals that Paul, like Jesus, believed that every part of Scripture, including every example, principle and psalm, originated from the mouth of God. Near the end of chapter four, Paul described the written Word of God codified in the Hebrew Scriptures as “living and powerful, and sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing even to the dividing asunder of both soul and spirit, and of both the joints and the marrow, and is able to discern the thoughts and intents of the heart” (Heb. 4:12). Earlier, he quoted Psalm 95:7-11, exhorting his readers to hear God’s voice speaking through these words. This same belief about written words being the living, authoritative utterances of God was later transferred to the writings of the apostles.

Apart from the many unrelated, non-biblical and popular interpretations (e.g., “inspired” preaching) often associated with the English words “inspired” and “inspiration” (which first appeared as a part of the English language in the 1400s AD), the term “God-breathed” literally means that every part of Scripture is the utterance (spoken word) of the living God set to writing. Paul’s choice of the word God-breathed holds many implications for the biblical writings:

1) It is only possible for the biblical texts (letters, syllables and words) to possess this quality as a result of God’s direct intervention in the writing process. God is so identified with the writing of the Bible that all the words penned by its human authors are literally His words.

2) The words of Scripture possess sacred qualities (e.g., infallibility, authority, truth, etc.), whether they were first orally revealed and later recorded or were immediately written by an author receiving revelation under the influence of the Holy Spirit. All of the biblical writings are marked by a unity of thought and purpose throughout that reflects God’s mind.

3) The term “God-breathed” restricts these divine qualities to the original writings (autographs) penned by God’s servants in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. Only these possess the infallible, inerrant and authoritative words and doctrines and truths given by God. Scribal copies (apographs) are God-breathed and possess the same divine qualities to the degree that they faithfully and accurately reflect the details and substance of the autographs.

4) “God-breathed” describes how the sacred quality of Scripture is distinct from that of all other non-biblical religious and secular writings.

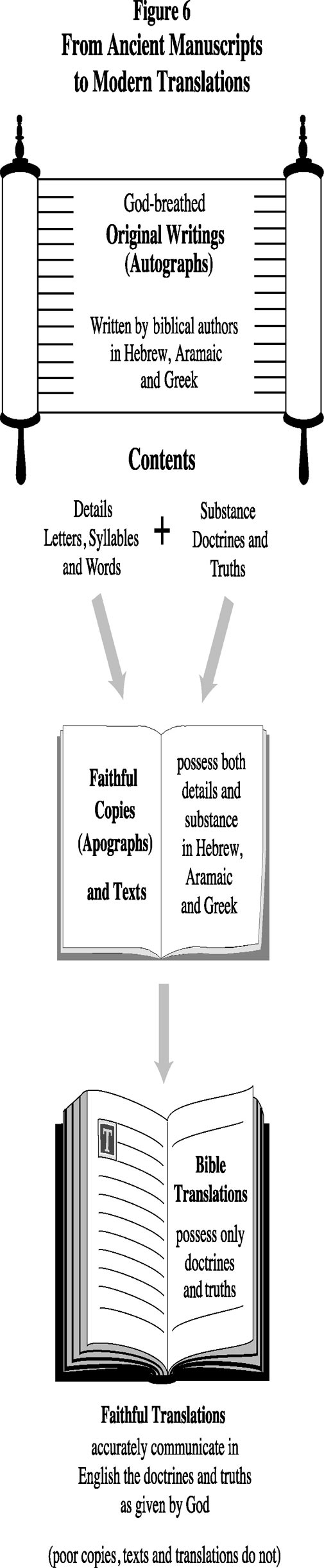

5) Translations can never be considered God-breathed because they do not possess the primary divine authorship of the autographs and apographs! Only the doctrines and truths of the autographs and apographs transfer in the translation process. As such, translations are subject to error and correction because they express divine truths in words that were not originally God-breathed (i.e., English). When doctrines and truths are translated accurately into other languages from the original texts, they possess the divine authority and sacred qualities of the autographs. (See Figure 6.)

Can we know whether the Bible is imprinted with God’s “breath”? Did He guide its writing? There are at least four major divine markers associated with God-breathed Scripture. These markers record the biblical authors’ conviction that the real author of their writings was God.

God Wrote Scripture by His Servants’ Hands

An excellent example of “God-breathed” in relationship to the Scriptures can be traced to Moses, the earliest known biblical writer. Exodus 17:14 reveals that God initiated the process of writing Scripture by instructing Moses to compose a short account of Israel’s deliverance from the Amalekites (Ex. 17:14). While this passage is the first time “writing” is mentioned in the Bible, it “clearly implies that it was not then employed for the first time but was so familiar that it was used for historic records” (Unger, “Writing,” The New Unger’s Bible Dictionary, p. 1374). The ten section headings in the book of Genesis that begin with the English word “generations” (Gen. 2:4, 5:1, 6:9, 10:1, 11:10, 27, 25:12, 19, 36:1, 37:2) indicate that written narratives, histories or books of people and events existed, which Moses had access to when writing his account of Genesis (Nelson, The King James Study Bible, p. 9). Such narratives and written accounts were clearly used by Moses in completing the volume known as the Book of the Law, which consisted of his five books (the Pentateuch).

Idiom is Key to God’s Authorship of Scripture: Though Moses wrote the entire Book of the Law, II Chronicles credits God with its authorship. In the eighteenth year of Josiah’s reign, Hilkiah the high priest found the Book of the Law amidst the temple debris. This book apparently had been “lost” for many years, possibly from the reign of the evil King Manasseh, Josiah’s grandfather. According to the account, “Hilkiah the priest found a book of the law of the LORD given by [Heb., by the hand of] Moses” (II Chron. 34:14, KJV). It is very possible that the book mentioned here contained the autographs of Moses’ writings.

Of particular note is the English word “by,” translated from the Hebrew idiomatic phrase “by the hand of.” Scholars have often ignored this idiom when translating the Hebrew text into English, thereby obscuring its meaning. Biblical scholar E. W. Bullinger explained that this Hebrew figure of speech is known as metonymy and occurs when “one name or noun is used instead of another, to which it stands in … relation.” In other words, the instrument—in this case the hand—represents the action it performs—writing. (Bullinger, “Metonymy,” Figures of Speech Used in the Bible, p. 538).

Hence, this passage could be rendered as “a Book of the Law of the LORD by” or “preserved in

the writing of” Moses. The point is that the book belonged to and was from God—it was merely written by Moses’ hand. The Hebrew idiom “by the hand of” portrays how God’s words and thoughts became a part of the written records of the Book of the Law. Moses was the instrument through whom God spoke and wrote.

Thus, as God “breathed” His words, they were imparted to Moses’ mind by the power of the Holy Spirit. In some cases, the words were first spoken by God, then communicated orally by Moses to the people and later transferred to vellum scrolls (e.g., Lev. 21:24, 24:23). In some instances God communicated His instructions to the Israelites in written form only (e.g., Ex. 34:27-28). This evidence confirms that Moses was the agent whom God used to write the Pentateuch, serving both as God’s spokesman and His scribe.

God also chose other men to serve as His spokesmen. The same Hebrew idiom associated with Moses’ writings is repeated throughout the Old Testament in relation to other prophets, illustrating that God often imparted His revelation to His people in written form.

Prophetic Schools Key to Writing: From the days of Joshua to the high priest Eli, the Bible tells us that “the Word of the LORD was precious in those days. There was no open vision” (I Sam. 3:1). Prophetic revelations from God were rare due to the rampant apostasy in Israel (Judges 21:25). During the time period of the Judges, the priesthood had degenerated to such a state that it no longer served as God’s instrument in teaching His ways to Israel. Because of the sins of Eli’s sons, Phinehas and Hophni, God rejected Eli’s house from serving before Him in the tabernacle (I Sam. 2:12-36).

After Samuel’s birth and his dedication to the LORD by his mother Hannah, the state of prophetic revelation in Israel changed dramatically (cf. I Sam. 1, 3). As the last judge and the first prophet since Joshua’s time, the Levite Samuel figures predominantly in the continuation of prophetic writing in Israel from the period of the Judges to the close of the Hebrew canon during the Medo-Persian rule of Judea.

The New Unger’s Bible Dictionary conveys the nature of this momentous turn of events: “Under these circumstances a new moral power was evoked—the prophetic order. Samuel, himself a Levite, of the family of Kohath (1 Chron. 6:28), and almost certainly a priest, was the instrument used at once for effecting a reform in the priestly order (9:22) and giving to the prophets a position of importance that they had never before held. Nevertheless, it is not to be supposed that Samuel created the prophetic order as a new thing before unknown. The germs … of the prophetic … order are found in the law as given to the Israelites by Moses (Deut. 13:1; 18:18, 20-21), but they were not yet developed because there was not yet the demand for them” (Unger, “Prophet,” p. 1041).

The reforms instituted by Samuel became the vehicle through which God worked in ensuring that His revelation was written down in the Old Testament era. “Samuel took measures to make his work of restoration permanent as well as effective for the moment. For this purpose he instituted companies, or colleges, of prophets [cf. I Sam. 10:5-6]. One we find in his lifetime at Ramah (1 Sam. 19:19-20); others afterward at Bethel (2 Kings 2:3), Jericho (2:5), Gilgal (4:38), and elsewhere (6:1). Into them were gathered promising students, and there they were trained for the office that they were afterward destined to fulfill. So successful were these institutions that from the time of Samuel to the closing of the canon of the OT [Old Testament] there seems never to have been wanting an adequate supply of men to keep up the line of official prophets. Their chief subject of study was, no doubt, the law and its interpretation—oral, as distinct from symbolical, teaching being henceforward tacitly transferred from the priestly to the prophetical order. Subsidiary subjects of instruction were music and sacred poetry, both of which had been connected with prophecy [and writing] from the time of Moses (Ex. 15:20) and the Judges (Judg. 4:4; 5)” (Ibid.).

Beginning with Samuel’s ministry, we find an increase in prophetic activity during which written records of God’s revelation and historical events were kept. Successive generations of prophets like Elijah and Elisha, who trained at and likely presided over these prophetic schools (II Kings 2, 4:38, 6:1-4), served as God’s chosen spokespersons and scribes to record the events of their time (II Kings 10:10; II Chron. 21:12). The father-son prophetic team of Hanani and Jehu probably belonged to the school of the prophets (II Chron. 19:2). Jehu chronicled the events that transpired during the reigns of several kings, and his writings form part of the book of Chronicles (II Chron. 20:34). Zechariah, a prophet who descended from the lineage of the famous priest and seer Iddo (Neh. 12:16; Zech. 1:1), wrote his book after the Babylonian captivity (520-519 BC). The prophetic writings were likely preserved and protected by the prophets until they turned them over to the Levites. After Ezra’s final editing of the Old Testament in the fifth century BC, the entire canon was committed to the Levitical scribes (Sopherim) for copying.

Writing in the New Testament: Paul’s letters were, as a rule, written by a secretary or scribe (e.g., Rom. 16:22). On four occasions in reference to his own written salutation in his Epistles, Paul preserved the idiom of the hand as a sign of their authenticity (I Cor. 16:21; Gal. 6:11; Col. 4:18; II Thess. 3:17). While 21 of the 27 New Testament books are classified as Epistles, the word itself is used in 11 passages to indicate the intimate form of correspondence sent by the apostles, elders and brethren to each other. On more than 90 separate occasions the apostles and their scribes made reference to their writing of a letter, narration or account that later became part of the New Testament (e.g., Rom. 15:15; I Cor. 14:37; I Tim. 5:18; II Pet. 3:1-2; II John 12; Jude 1:3; Rev. 1:1-3). In all these instances, Peter testified that the apostles and their scribes followed the same pattern as the holy prophets of ancient Israel in writing Scripture—they were all moved by the Holy Spirit, the “breath of God,” to record the words of God (II Pet. 1:20-21).

God’s Servants Professed to Speak and Write on God’s Behalf

The act of writing only tells part of the story of the Bible’s divine authorship. Bible researchers have counted more than 3,800 times that the writers of the Old Testament used various formulas to describe what they spoke and later wrote as the utterances of God (Connelly, The Indestructible Book, p. 191). An electronic digital Bible search program such as Online Bible can readily locate where variations of the following divine formulas appear throughout the writings of the Old Testament: “The word of the LORD came unto him, saying,” “Thus says the LORD,” “The burden of the word of the LORD,” “The word of the LORD by,” “Hear the word of the LORD,” “Thus has the LORD spoken unto me” and “Thus says the LORD of hosts,” etc…

Pentateuch/Joshua: The five books of Moses (Pentateuch) are unquestionably represented as the Word of God. In at least 65 instances, the book of Genesis uses clauses that bear witness to this fact, including “God said,” “God spake,” “the LORD said,” “the LORD God said,” “the LORD God commanded,” “the word of the LORD came,” and “the Angel of the LORD said.”

Moses recorded God’s words and the events that transpired during Israel’s wilderness journey as God commanded him (e.g., Ex. 17:14, 34:27, 32; Num. 33:1-2; Deut. 31:19, 22). An electronic digital Bible program searching the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy tallies at least 160 times that God communicated His will to ancient Israel through Moses. These instances are introduced with expressions like “And the LORD spoke unto Moses, saying, ‘Speak to the children of Israel.’ ”

Moses was unique among the Old Testament authors and one of the few prophets in Israel to have seen God “face-to-face” and to have spoken with Him as a man speaks with his friend (Ex. 33:1; Num. 12:8; Deut. 34:10). In contrast, God told Moses’ siblings (Aaron and Miriam) that He would make Himself known to future prophets in visions and dreams (Num. 12:6). Moses’ ministry became the foundation for all subsequent prophetic ministries and the standard by which they were judged (Deut. 18:18-22).

Moses’ successor, Joshua, also spoke face-to-face with God on occasion (e.g., Josh. 5:13-15). Whether at the tabernacle or elsewhere, conversations often commenced with the phrase “And the LORD said unto Joshua.” Joshua recorded in the Book of the Law all of God’s words and Israel’s military campaigns, which were conducted under God’s guiding hand, which were then given to the high priests (Josh. 24:26). The English word “Now” in Joshua 1:1 is actually translated from the Hebrew conjunction “And,” indicating that the book of Joshua is really a continuation of the Pentateuch and closely linked to Moses’ writings.

Other Prophets: Other Old Testament prophets professed to speak the words of the LORD in their prophetic forecasts and stern warnings, which called on both Israel and Gentile nations to repent (e.g., Isa. 6:8-9, 7:3, 8:1; Jer. 1:2-7, 2:1, 7:1, 11:1, 14:1; Ezek. 1:3, 2:1-7; Dan. 1:17, 2:19-23; Hos. 1:1; Joel 1:1; Amos 1:1-3, 3:7; Obad. 1:1; Jonah 1:1; Micah 1:1; Nah. 1:1; Hab. 1:1; Zeph. 1:1; Hag. 1:1; Zech. 1:1; Mal. 1:1).

The book of Isaiah offers one of the most graphic examples of the divine authorship of Scripture. Chapters 40-66 are written from God’s perspective, presenting the reader with an image of God writing a letter to exhort His people. King David attested to the divine authorship of his psalms, asserting that God actually put His Word in his tongue (II Sam. 23:1-2). In Psalm 45:1, the sons of Korah, the Levitical servants at the temple and the writers of many psalms, also claimed that their tongues were like the pens of skillful writers, indicating how God blessed and used their ability to write poetic songs for His glory. God gave David’s son Solomon wisdom and understanding to compose 3,000 proverbs and 1,005 songs (I Kings 4:29,32; Psa. 72 title, 127 title; Prov. 1:1, 25:1; Eccl. 1:1, 12:9).

The Four Gospels: The Bible records that in these last days God has spoken to us by His Son Jesus (Heb. 1:1). In the autumn of 26 AD, Jesus, who was God manifested in the flesh, began His ministry as the Apostle and Messenger of God the Father (John 5:36-38, 43, 7:16, 8:42; Heb. 3:1). Throughout His ministry, Jesus declared that He was speaking the words of the Father Who had sent Him: thus revealing the Father’s message to His apostles and those who heard Him (John 8:26-28, 42-43, 12:49-50, 14:10, 23- 24, 17:8, 14). John the Baptist, who prepared the way for the Lord, testified of Jesus, “He Whom God has sent speaks the words of God; and God gives not the Spirit by measure unto Him” (John 3:34). And Jesus also told His disciples, “The words that I speak to you, they are spirit and they are life” (John 6:63).

The Online Bible lists at least 320 references from the Gospels that are marked by expressions such as “I say unto you,” “And Jesus answered and said,” “Verily, verily (truly, truly)” and “He said unto them.” These markers notify readers of instances when Jesus spoke with divine authority and introduced a spiritual truth to His apostles, the gathered crowds and others.

Luke particularly expressed a conviction that his Gospel had spiritual importance when he claimed that he had “accurately understood everything from the very first.” Paul also held a high view of Luke’s Gospel and assigned to it the same divine authority as the book of Deuteronomy (I Tim. 5:18; cf. Luke 10:7). The apostle John claimed that the purpose of his Gospel was to lead readers to “believe Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God.” John and various individuals alive at the time testified to its authenticity (John 21:24).

Acts of the Apostles: In many respects, the book of Acts is equivalent to the Old Testament historical books (Judges, Samuel, Kings, etc.). Luke, its writer, gathered material from various sources to chronicle important events in early Church history. He was an eyewitness on many occasions to events that transpired on the apostle Paul’s missionary travels. One unique marker of this book is its history of the spread of the Gospel (i.e., Word of God) from Jerusalem to faraway places, such as Rome, through the work of the apostles and early disciples of Jesus Christ (cf. Acts 2 and 28).

Following Jesus’ ascension in 30 AD, Luke established that the message the apostles taught with boldness in the Temple area and to the brethren was the Word of God (Acts 3-4). The apostles dedicated themselves to prayer and ministry of this same word (Acts 6:4). The Samaritans received the Word of God preached by the evangelist Philip (Acts 8:4-5, 14, as did Cornelius and his household from Peter (Acts 11:1). It was this same word that Paul preached both in the synagogues and elsewhere on his three missionary journeys (Acts 13:5, 7, 44, 46, 48, 49; 15:35, 36; 16:32; 17:13; 18:11; 19:10). Luke wrote that the Gospel spread rapidly and widely (Acts 12:24, 13:49, 19:20), and that many Jews living in Jerusalem and a great number of Levitical priests became disciples of Jesus (Acts 6:7).

Pauline and Other Apostolic Works: God specifically chose Paul as an instrument for proclaiming His Word to the Gentiles (Acts 9:15). He abode for a period of time in the wilderness of Arabia where Jesus personally revealed specific truths to him to enable him to accomplish his divine mission (Acts 26:16; Gal. 1:12, 17-18). Paul is considered the towering figure of early Christianity, and his books comprise over 50 percent of New Testament writings. It is from his published works that we often obtain a greater understanding of the divine authorship of Scripture.

The book of I Thessalonians displays one of the most powerful examples of Paul’s conviction that what he wrote was God-breathed. Paul began by praising the Thessalonians for their “work of faith” (I Thess. 1:3) and for having received the message he had preached not “as the word of men, but … the word of God” (I Thess. 2:13). He repeated Jesus’ words from Luke 10:16 in warning the brethren that whoever rejected his apostolic commands rejected the Father (I Thess. 4:8) and solemnly commanded the brethren by the Lord to read his Epistle in the congregation (I Thess. 5:27). Paul made similar claims of divine sanction for his other Epistles. To the Corinthians he wrote: “Did the Word of God originate with you? Or did it come only to you and no one else? If anyone thinks that he is a prophet or spiritual, let him acknowledge that the things I write to you are commandments of the Lord” (I Cor. 14:36-37).

The apostle Paul opened almost all his Epistles with a prescript of his divine calling and the divine authority with which he wrote, like the one in Romans: “Paul, a bondservant of Jesus Christ, a called apostle, set apart to preach the gospel of God” (Rom. 1:1). James, Peter, John and Jude likewise claimed divine authority for the writing of their General Epistles. In the book of Revelation, the apostle John specifically informs us that the visions, words and prophecies he recorded were the “revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave … by His angel to His servant John” (Rev. 1:1).

References to God and the Holy Spirit Having

Spoken Through His Servants’ Writings

References: Mark 7:6 (Isaiah), Mark 7:10 (Moses); Mark 12:36 (David); Acts 1:16 (David), Acts 4:25-26 (David), Acts 28:25-27 (Isaiah); Rom. 9:25 (Hosea), Rom. 10:5 (Moses), Rom. 10:19-21 (Moses, Isaiah), Rom. 11:9 (David).

Statements That Equate Scripture as the Utterances

of God and Vice Versa

Paul and Luke assert that the Scriptures were the written oracles of God (Acts 7:38; Rom. 3:2; Heb. 5:12). In agreement with this first-century mindset, Jesus and His apostles affirmed the divine authority of the Old Testament for the children of Israel, the Jews and early believers by referring to its writings on more than 70 occasions with the clauses “it is written” and “have you not read.” Warfield explained that the authority of the Old Testament “rests on its divinity and its divinity expresses itself in its trustworthiness; and the NT [New Testament] writers in all their use of it treat it as what they declare it to be—a God-breathed document, which because [it is] God-breathed, is through and through trustworthy in its assertions, authoritative in all its declarations, and down to its last particulars, the very word of God, His ‘oracles’ ” (Bromiley, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, p. 844).

During his discourse, Stephen rehearsed how Moses had received the “living oracles” (laws, commandments, statutes and judgments) from God on Mount Sinai for ancient Israel (Acts 7:38). The words “living oracles” indicates that for Stephen, Moses’ writings, after centuries of copying, still possessed a living, divine authority as having come directly from the mouth of God as opposed to the dead letter of Jewish unbelief (Acts 28:26-27; II Cor. 3:14-15). Stephen used this expression to impress upon the Jewish leaders that, like their ancient ancestors, they had hardened their hearts and rejected the living utterances (voice) of God as recorded by Moses and later the prophets under influence of the Holy Spirit (Neh. 9:30; Acts 7:39, 51; Heb. 3:8-19). The Bible confirms that this is exactly what occurred when ancient Israel violated their covenant with God (Ex. 19:5; Deut. 30:2, 8, 10. 20; Dan. 9:11-12).

In his introduction to the book of Romans, Paul disclosed that salvation is a matter related to a person’s heart, not ancestry (Rom. 2:28-29). In spite of this truth, Paul explained that the Jewish people still possessed an advantage over non-Jews, namely, they were entrusted with the entirety of the written utterances of God penned by the Old Testament authors (Rom. 3:1-2). Paul’s remarks become even more relevant when we understand that the standard Old Testament scrolls were stored in the temple area since Ezra’s time. Scribes made official copies from these scrolls, which were then sent to the synagogues in the Diaspora. Paul insisted that Jewish unbelief did not invalidate the testimony of the Hebrew Scriptures as God’s living oracles (Rom. 3:3-4).

Usage Expanded: The gift of prophecy, both the foretelling and preaching of divine oracles, is listed immediately after the gift of apostleship and forms a part of the foundation of the Christian Church (I Cor. 12:28; Eph. 2:20, 3:5, 4:11). While the expression “oracles of God” was restricted elsewhere to the Old Testament writings, Peter expanded its meaning to include the spoken and written words of the New Testament prophets, namely, the apostles.

The expanded usage of the word “oracles” can be understood in its broadest terms by briefly surveying Peter’s and Paul’s earlier letters, almost all of which Peter had in his possession when he wrote his Second Epistle (II Pet. 3:15-16). The progression of the apostolic word and meaning can be observed in Peter’s First Epistle, where he wrote that though the promise of salvation had been revealed to the holy prophets of Israel by Christ through the Holy Spirit, they did not fully understand the grace about which they had prophesied (I Pet. 1:10-11). Rather, it was left to the New Testament apostles to announce the fulfillment of the written Old Testament prophecies concerning the grace and sufferings of Christ in their preaching of the Gospel (I Pet. 1:12).

In I Corinthians, Paul described himself, his fellow apostles and other faithful ministers of Jesus Christ as stewards or dispensers of God’s divine truth: “Let every man regard us as ministers of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God. Beyond that, it is required of stewards that one be found faithful” (I Cor. 4:1-2). Gentile converts would clearly have understood that Paul was comparing the truth he offered to the false knowledge of the pagan mystery religions at Corinth. In contrast to Paul’s methods, the pagans concealed their religious mysteries from all except the fully initiated.

Paul used the expression “mysteries” (Gk., mysterion) in a general sense to refer to God’s truth previously kept hidden until God decided to reveal it. Paul told the Ephesians, “You have heard of the ministry of the grace of God that was given to me for you; how He [God] made known to me by revelation the mystery (even as I wrote briefly before, so that when you read this, you will be able to comprehend my understanding in the mystery of Christ), which in other generations was not made known to the sons of men, as it has now been revealed to His holy apostles and prophets by the Spirit” (Eph. 3:2-5).

Paul and the other apostles followed the example of Jesus, who frequently declared to His “stewardship” of the divine words that the Father had committed to Him to preach to the multitudes and to reveal to His true disciples (e.g., John 12:49-50, 17:8). Jesus told the apostles on one occasion, “To you it has been given to know the mystery of the kingdom of God; but to those who are without, all things are done in parables” (Mark 4:11). The prophets of ancient Israel also professed to deliver the burdens (Hebrew, oracles) or secret plans of God in their oral and written messages. The prophet Amos wrote, “Surely the Lord GOD will do nothing unless He reveals His secret unto His servants the prophets” (Amos 3:7).

On the night that Jesus was betrayed, He told the apostles, “No longer do I call you servants because the servant does not know what his master is doing. But I have called you friends, because I have made known to you all the things that I have heard from My Father” (John 15:15). Although Jesus’ words reflect on His past ministry, the entire context of John 14-17 shows that His words held significance for the apostles’ future prophetic ministries. The fullness of Jesus’ revelation was confirmed by the apostles in their spoken messages, validated through the miracles and signs that followed them (Acts 2:43; Heb. 2:3-4) and were affirmed in their writing of the New Testament. The Bible confirms that the apostles were faithful stewards in proclaiming God’s mysteries, specifically the Gospel message, entrusted to them by Christ (Luke 12:42).

Finally, Jesus said that He would send the Holy Spirit, which would bring to remembrance everything He had told them, lead them into all truth and disclose to them things to come as received from Him (John 14:26, 16:12-14). It is Jesus Christ, then, Who is the real author of the New Testament. Its words are God’s as spoken by His Son (Heb. 1:1) and revealed by the Holy Spirit. It was to these oracles and God’s written utterances in the Old Testament that the true disciples of Jesus Christ throughout all generations would make their appeal.

Contact Webmaster

Contact Webmaster Copyright © 2025 A Faithful Version. All Rights Reserved